February 10, 2026

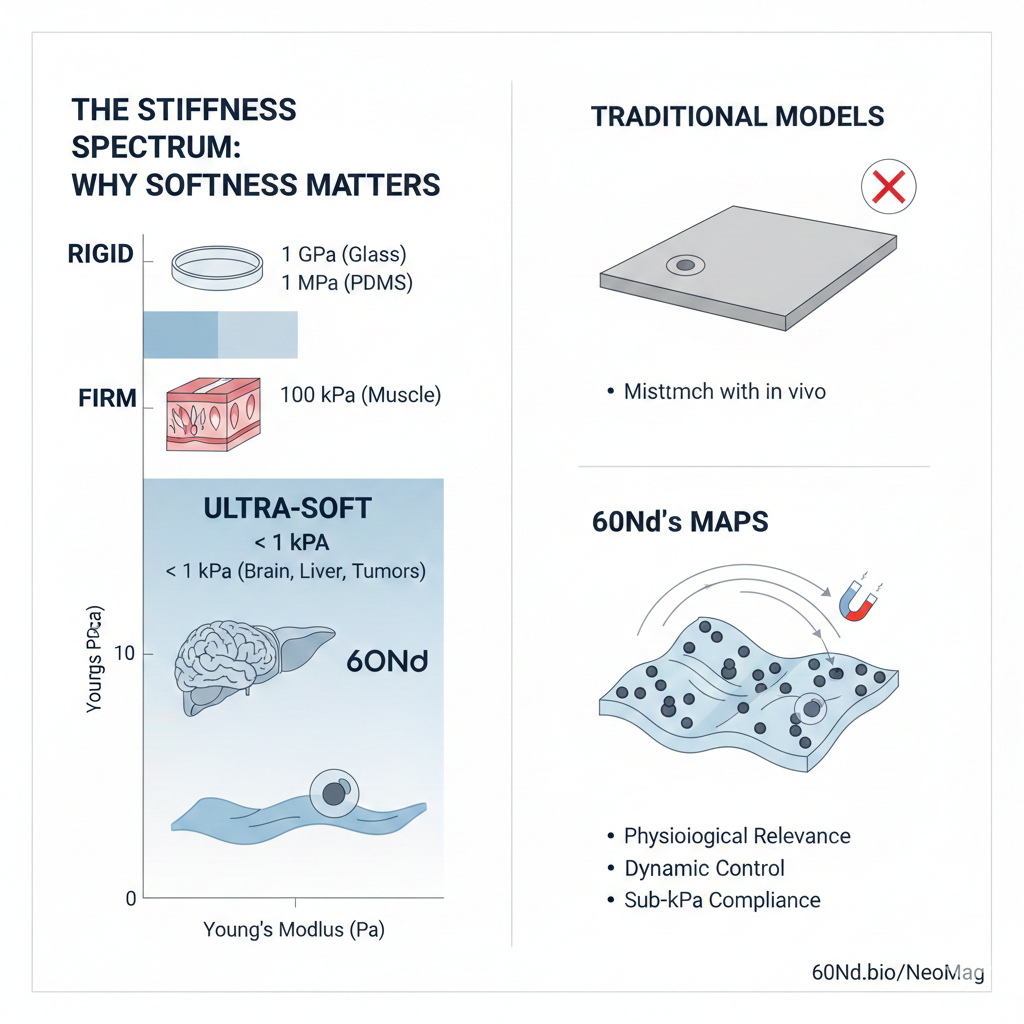

In our previous posts, we established that biology is inherently mechanical. However, there is a "missing link" in most in vitro models: the substrate. For decades, researchers have used Materials like glass or stiff polymers (like PDMS) to culture cells. But there’s a problem: the human body is not made of plastic.

Most of our tissues—especially the brain, liver, and tumors—are incredibly soft. To truly understand how cells behave, we need to culture them on materials that feel like home. This is where Ultra-Soft Magneto-Active Polymers (MAPs) come in.

At 60Nd, we have developed a proprietary range of elastomers with extreme compliance. While standard cell culture surfaces have a Young’s modulus in the range of Mega-Pascals (MPa) or Giga-Pascals (GPa), our MAPs operate in the sub-kiloPascal (< 1 kPa) range.

Why is this a breakthrough?

Our MAPs are composite materials where magnetic micro-particles are embedded within an ultra-soft elastomeric matrix. When NeoMag applies a controlled magnetic field, these particles react, causing the entire substrate to deform.

Unlike traditional "stretchers" that rely on bulky vacuum pumps or mechanical pullers, our approach is:

The challenge isn't just making a soft material; it's making it stable and reproducible. Through our research (rooted in ERC-funded foundations), we have solved the common issues of particle sedimentation and batch-to-batch variability. This ensures that when you run an experiment in Madrid, the mechanical stimulus is identical to one run in Boston.

By combining the "softness" of life with the "control" of magnetism, NeoMag allows researchers to stop "guessing" mechanics and start "programming" them.

What’s next?

Softness is only half the story. In our next post, we will dive into Complex Deformation Modes: why simple stretching isn't enough to simulate the real complexity of a beating heart or a growing tumor.

Follow 60Nd for more insights into the future of Magnetomechanics.